True tech is the new true crime. Any tycoon who’s any tycoon has had their rise turned into a drama — even Daniel Ek. Netflix’s 2022 series The Playlist portrays Spotify’s low-key co-founder and chief executive as a kind of geek-savant determined to make his dream of a music streaming service reality in the face of hostile scepticism from the big record labels. Having watched a few episodes on the flight to Stockholm (it’s more gripping than it sounds), I ask what he made of it.

“I don’t know,” Ek says. “I haven’t watched it.”

Right. Ek, 41, both embodies and defies Jantelagen, the don’t-get-above-yourself Scandinavian social code. He is mild-mannered, unflashy, seemingly uninterested in the usual trappings of ego. He arrives for our meeting in central Stockholm dressed down in T-shirt, jeans, trainers and chunky specs, making him indistinguishable from the other trendy dads who populate the area. Tick, tick, tick.

But Ek — pronounced Eek — is also the restless, relentless entrepreneur who set out to change the way we listen to music in 2006, while still in his early twenties. He built Spotify into the $69 billion David that, depending on your point of view, saved the music industry’s Goliath from internet piracy or delivered the slingshot coup de grâce by inserting itself between artists and audiences — paying the former as little as $0.003 per stream. Per Sundin, former boss of Universal Music Sweden and the first executive to partner with Spotify, described Ek as “Jesus coming to town”. Radiohead’s Thom Yorke dismissed his gambit as “the last desperate fart of a dying corpse”.

Spotify, which has 626 million active users, is on course for its first ever profitable year, having bled money until now paying licensing fees to labels, hiring staff around the world and splurging on growth areas such as podcasts. Its soaring share price has made the shy coder from Ragsved — an unlovely suburb south of the Swedish capital — a billionaire and a business celebrity.

Ek has two daughters, Elissa and Colinne, with Sofia Levander, a Swedish writer and journalist. The couple’s wedding at Lake Como in 2016 was officiated by Chris Rock and attended by the Facebook founder, Mark Zuckerberg. Bruno Mars provided the entertainment — Jantelagen enforcers, avert your gaze. Ek has played table tennis with Justin Bieber and hung out with the dubstep star Skrillex.

“Solving problems” is, he says, what interests him most, and he’s not stopping at music. In 2021 he jointly set up an investment firm called Prima Materia to back promising European start-ups. One, slightly incongruously, specialises in AI-based software for the defence sector and is helping to develop AI capabilities for drones in Ukraine. The others are in the industry Ek wants to shake up next: healthcare. The man who helped kill off your CD collection could soon be coming for your GP.

“You read about all the horrible stuff that’s happening around the world and the reality is, most things are becoming better, but there are a few glaring areas where that’s not true,” Ek says, in the American-inflected English he learnt from MTV. “Healthcare is one of the worst. For a long time we were getting rapidly improving life expectancy. But if you look at it in the last few years, it’s going in totally the wrong direction. And there’s no obvious fix because all the current system tries to do is basically pile on even more people, even more costs, even more drugs.”

While these thoughts were swirling in his head, people would often tell him they thought Spotify was amazing. “And I kept responding with the same thing — ‘Yeah, it’s really great, but it’s not like we’re saving lives.’ And lo and behold, I started thinking, well, why am I not saving lives?”

Enter Neko Health, which has two clinics in Sweden and opened a third in Marylebone in London last Wednesday. We meet at his newest site in Stockholm, next to a teashop on an upmarket street, Sibyllegatan. It is a bright space with white walls and organic curves — the healthcare equivalent of an Apple store. Soft instrumental music gives it the added feeling of a spa.

The starting point for Neko is a belief that an increasing number of consumers (note that word) will pay a decent but not credit card-busting sum (£299 per check-up in London) for a regular health screening that goes beyond what most taxpayer-funded GPs carry out. Ek mixes in Silicon Valley circles and knows well the billionaire class’s obsession with longevity — the hyperbaric oxygen chambers, the red-light therapy beds. “There are a lot of tools available for the ultra-wealthy elite, but I’m interested in doing this to bring the cost down, so it can be accessible,” he says.

Not as accessible as free healthcare, though. “When we started Spotify, no one paid for music,” Ek says. “The reality — people were just stealing music. The big uncertainty here was, is anyone going to want to pay for healthcare that they get for free? If you just ask people on the street [in Sweden], they would be, like, ‘Why would I want to do that? We’re living in the world’s best healthcare system.’ And then we asked them, ‘So are you happy about so-and-so?’ They’d say, ‘No, no, no, it’s terrible.’ ”

Ek says that as with music, being an outsider means he sees things “from a totally different viewpoint”. “Elon” — he refers to Musk by his first name — “didn’t have any experience building cars. He was building software companies. But if you think about an EV today, it’s a computer on wheels. That is his vision … We think about healthcare very similarly — how do we use all these advancements to make the process better for the doctor making the diagnostic decisions, but also fundamentally for the patient, the consumer? So much of what actually happens [at the moment] isn’t to the benefit of either. It’s the system that decides, ‘This is what this can cost.’ ”

Raised by a single mother who worked at a childcare centre, Ek got his first guitar aged four and his first computer aged five. By the age of 14 he was a skilled programmer. He was earning thousands of dollars making websites while still at school and, having been turned down for a job by Google at 16 because he did not have a university degree, started his own online marketing company.

Ek minted his first million at the age of 23 when he sold his online advertising company Advertigo to Tradedoubler, a Swedish marketing platform. He tried out the playboy lifestyle, buying a red Ferrari and splashing money in nightclubs, but found it left him “completely depressed”. “I realised the girls I was with weren’t very nice people,” he told an interviewer ten years ago.

Ek retreated to a cabin near Ragsved and contemplated what to do next. Conversations with Martin Lorentzon, Tradedoubler’s co-founder, led them to launch Spotify together. Sweden was its natural birthplace because it was a hotbed of music piracy. In the late 1990s the Swedish government rolled out high-speed broadband as an essential public utility and funded schemes to enable every citizen to buy a computer. This coincided with the advent of file-sharing sites such as Napster in the US and Sweden’s Pirate Bay. Ek was part of a generation that stopped buying CDs and gorged itself on free music — in his case, working backwards from Metallica to Led Zeppelin, King Crimson, David Bowie and the Beatles, then forward again to the Eurythmics and the Sex Pistols.

As this happened to varying degrees worldwide, the music industry’s revenues crashed from an all-time high of $22.3 billion in 1999 to $18.1 billion in 2006. Ek and Lorentzon set about trying to design a user-friendly alternative to piracy that would be based on commercial deals with the record labels, and embarked on two years of painful negotiations. A group including Universal Music, Sony and Warner Music eventually agreed to license their catalogues to Spotify in exchange for a 70 per cent share of its income and an ownership stake of 18 per cent. Sundin, the former head of Universal Sweden, told his team: “If this f***s up we’re going to be dead, so let’s go all in.”

Spotify launched in Sweden in 2008, the UK in 2009 and the US in 2011, and is now in 184 countries. There was initially carping from artists who seemed to see Spotify as a new corporate middleman, not least from Taylor Swift, who temporarily pulled her music from the platform in 2014. Since then, music industry revenues have enjoyed a U-shaped recovery. They hit $28.6 billion last year, according to the IFPI trade body, with streaming generating more than two thirds. Swift, who put her music back on Spotify in 2017, accounted for one in every 78 streams in the US.

Spotify claims it has paid $48 billion to the music industry since its founding. It says the number of artists earning more than $1 million a year has almost tripled since 2017. But other research suggests that Spotify’s winners are bunched together tightly, with a long tail of artists earning hardly anything. The music analytics business Chartmetric reckons that more than 80 per cent of the 9.8 million acts on Spotify get fewer than 1,000 monthly listens — and that only Swift and the Weeknd have ever surpassed 100 million.

To put that in context, Spotify pays roughly $0.003 to $0.005 per stream. Far Out Magazine calculated that a single musician making one album a year at a cost of £8,000 would need 2.4 million monthly streams to earn a liveable wage. A throwaway remark by Ek on X in May that “the cost of creating content” was “close to zero” sparked anger. Cheryl B Engelhardt, a new age singer-songwriter, told Ek to “please get a clue and maybe talk to REAL musicians”.

Spotify’s shares, which floated in 2018, boomed alongside the pandemic mania for tech stocks and subscription services, then collapsed as inflation and higher interest rates made investors panic about the sustainability of loss-making companies. They have since bounced back, quadrupling since the start of last year as Ek culled 2,000 staff — about a quarter of the workforce — and partially reversed a $1 billion bet on podcasts. Among the podcasts axed was Archetypes, a show by the Duke and Duchess of Sussex that ran for just 12 episodes. Bill Simmons, head of podcast innovation at Spotify, called Harry and Meghan “f***ing grifters”.

Ek told his troops that Spotify was “in a very different environment” from the past and that “being lean is not just an option but a necessity”. “It’s never fun to go through a journey where you have to let go of super-talented people, and it’s been sort of up and down,” he tells me. “But I think it comes back to the most important thing we’ve known all along — that we can be not just a great product but also a great business.”

A far more significant source of controversy has been Joe Rogan, the libertarian firebrand who signed a $100 million exclusivity deal with Spotify in 2020 and is the streamer’s most popular podcaster. Rogan has repeatedly caused reputational problems for Spotify — including by hosting the far-right conspiracy theorist Alex Jones and seeming to spread misinformation about Covid, which prompted Joni Mitchell and Neil Young to withdraw their music from the service for two years. After a compilation video in 2022 showed him using a racial slur, Rogan apologised and some old episodes were taken down. Mitchell and Young returned this year, a capitulation some saw as underlining Spotify’s unshakeable power over artists — although Young criticised its audio quality, describing it as “the #1 streamer of low res music in the world”.

Ek won’t comment on Rogan but offers his general thoughts on how he handles crises. “The value of what you’re building is the sum of all the problems you’re solving,” he says. “You’re going to encounter lots of different problems. But when you do solve those problems, you create a lot of value. This is the hardest thing for people from the outside to understand. That is what calms me.”

Another passion is Arsenal. Ek has followed the north London club since the 1990s, when his countryman Anders Limpar played there as a midfielder. In 2021 Ek, who had the support of alumni including Thierry Henry, said he was “very serious” about wanting to buy Arsenal from the American billionaire owner Stan Kroenke and his family. They said they were not interested in selling. Is that dream dead?

“For now, for sure,” Ek says. A Delphic smile. “But as a fan, I’m incredibly happy that they’re doing so well. It’s sad on one hand, but I’m incredibly happy anyway.”

Spotify’s co-founder was an early adopter of health gadgets such as the Fitbit sleep tracker and Wii Fit weight scales. As his streaming baby grew, he spent his spare time not driving around in a Ferrari or doing shots in nightclubs but reading PhD papers on genetics and DNA sequencing.

More than a decade ago Ek described the way doctors treated patients as “close to witchcraft”. He was baffled by the medical establishment’s reluctance to use data and its focus on cure rather than prevention. Eventually he decided to do something about both.

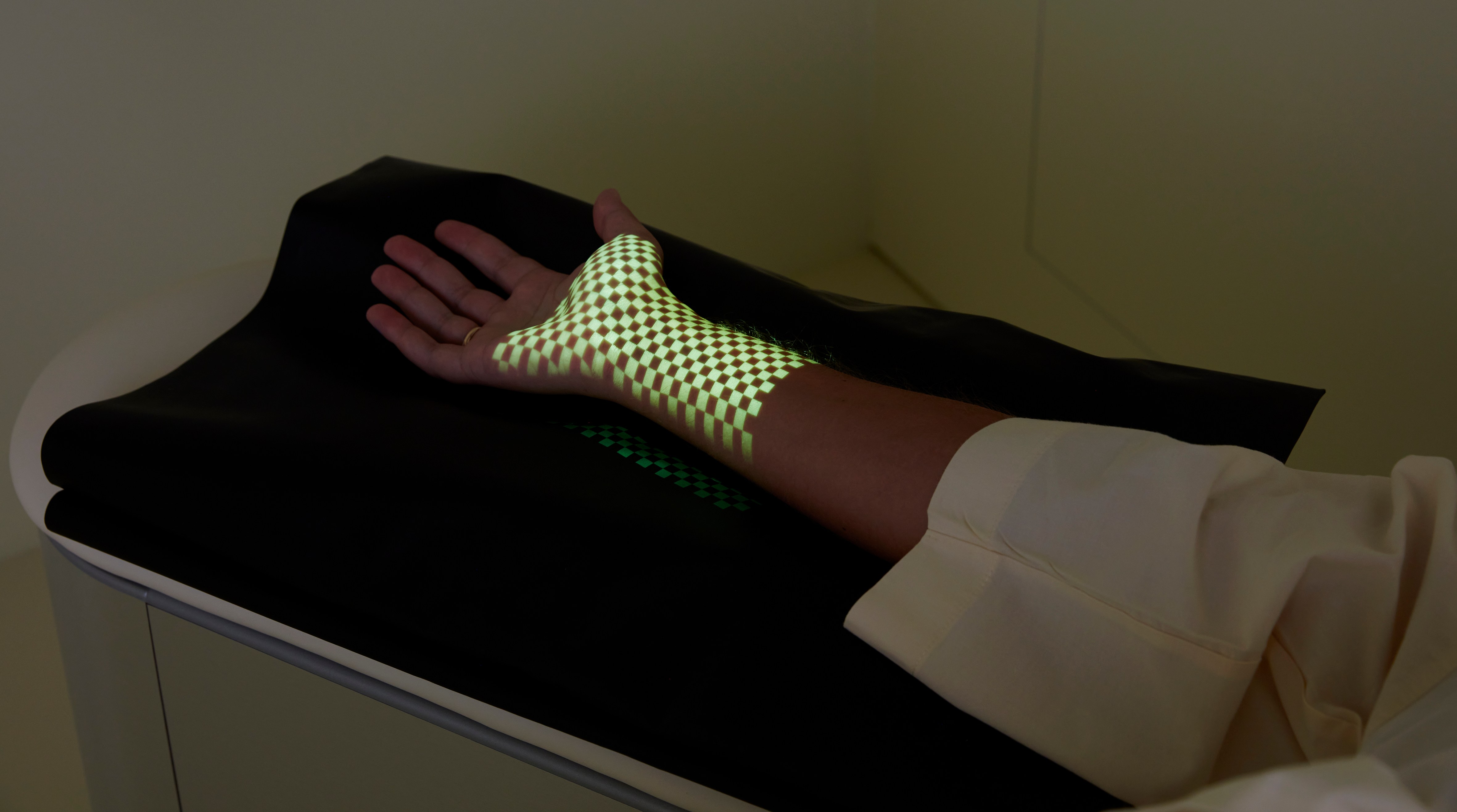

Neko offers what it calls “a preventative health check for your future self”. This involves the photographic mapping and indexing of skin blemishes; a blood test; tests for grip strength, eye pressure and blood pressure; and an electrocardiogram (ECG) to measure the heart’s rhythm and electrical activity. The results are immediate, I am told — even for the blood sample, which is analysed in 15 minutes. So I put it to the test.

I am given a white robe and slippers and directed to the scanning chamber, a circular space where I face a bank of what look like giant iPhone cameras. The door slides shut and a disembodied female voice with an English accent instructs me to close my eyes. There is a flash of heat and light as the cameras take more than 2,000 high-resolution images of my body. The chamber door opens again and I am asked to recline while Neko’s technicians take the blood sample and do the ECG.

Finally Dr Andreea Valdman, Neko’s lead GP, talks me through the results in front of a touchscreen featuring an avatar of my body and my vital stats. She’s surprised that my blood pressure and cholesterol level are so good, given the eating and drinking habits I’ve confessed to. But she says my BMI is “a bit elevated” (thanks) and reminds me that a healthy weight is crucial for cutting the risk of heart disease and diabetes.

Along with the majority of the 2,700-plus people scanned in Neko’s first year, I will leave reassured yet infused with a desire to improve my scores next time. One in ten, however, will find out they have a serious condition such as diabetes. One in a hundred will discover a life-threatening problem requiring urgent treatment.

Hjalmar Nilsonne, a serial entrepreneur and Ek’s partner in the venture, tells a story about a man whose scan showed “a major cardiovascular anomaly”. Neko referred him to Sweden’s public healthcare system; he underwent surgery a fortnight later. “The cardiologist told him he would have been dead within eight months if it hadn’t been found,” Nilsonne says.

Ek says that Nilsonne “does most of the work” — which is just as well, given that Ek’s day job is overseeing a New York-listed business with revenues of more than $14 billion and 7,300 staff.

Nilsonne comes from a family of doctors, and argues that early detection is good for creaking healthcare systems as well as individuals because treatments at a more advanced stage tend to be more costly and dangerous. The NHS waiting list, with its 7.6 million outstanding treatments, is a source of national frustration in the UK. But even in Sweden, despite its higher taxes and reputation for better public services, 17 of the 21 regional healthcare boards are expected to be in financial deficit this year.

“This is not fundamentally a political problem because it’s the same in Sweden and in the UK and in Tokyo,” Nilsonne says. “It’s literally illegal not to do an MOT on your car, but when it comes to our health we don’t do anything. Prevention is the oldest idea in medicine — if you go back to the Hippocratic oath, there’s a line in there that prevention is always preferable to cure.”

Sceptics might say that Neko offers no more — in fact, probably a fair bit less — than the private doctors of Bupa and Harley Street. That’s where Ek’s Spotify experience comes in. He wanted to make “healthcare as individualised as your Spotify playlist”.

There is immediacy: just as Ek ordered Spotify’s programmers to get the “latency” between the play button being pressed and a song starting to 0.2 seconds, so he and Nilsonne determined that the results of all Neko’s tests had to be delivered on the spot.

And there is cost. Neko is priced more cheaply than a traditional private doctor or rivals such as Prenuvo, whose MRI scanner Kim Kardashian hailed on Instagram as a “life-saving machine” last year. Competition is hotting up, however: Bupa is launching what it calls a “Netflix-style GP subscription” for £16.66 a month.

There are some big differences between Neko and Spotify. Software companies are massively scalable because the product can be replicated at almost zero cost. Neko requires expensive staff and equipment. And whereas few would object to record companies analysing Spotify users’ listening habits, you can imagine the rows that could break out if Neko customers’ data were to find its way to third parties such as employers or insurers. (Neko says it never shares data for commercial purposes and does so only for storing on IT providers’ servers or when it needs to meet legal obligations, such as for supervision by the Care Quality Commission.)

Will Neko and its ilk be more than gimmicks? My guess is that they won’t lure patients away from private doctors so much as bring in a new type — the kind of white-collar professional who loves their Apple watch and Oura ring, and enjoys the gamification of their health data.

For Ek, an emphasis on longevity is not the point. “We think it is possible to increase people’s lifespans if we go preventative — but more important for me than focusing on lifespan is increasing health span,” he says. “I would rather not live longer but have every single day up until the day I die be one where I’m healthy. The opposite is where I sit and maybe live 20 years longer, but the last 20 years are pretty awful and I can’t really do much with those years anyway.” The extended health span “is the vision of what we’re trying to accomplish for everyone”.

It probably won’t have Netflix scrambling to commission a sequel to The Playlist. But it could be big business — and who knows? Sweden’s streaming king might just save a few more lives while he’s at it.nekohealth.com